My toughest six-day race

By Walter Rutt

For twenty-five years, I have been roaming the world as a racing driver. For twenty-five years, a film of rapid-fire events has been playing before my eyes, and I often find it difficult to separate the events from one another. It often takes me a long time to figure out where and when this or that event crossed my path and what feelings inspired me at the moment I experienced it. And yet, many events stand out from the wealth of memories. Often they are small things, often just a word or a joke, but these things stand out above all other memories in my mind's eye.

If you asked me which was my best race, I would have to think about it, but I could answer the question of which was my hardest race immediately. I have competed in many 144-hour races on both sides of the ocean, I have experienced so much in these races, and I would be able to recall many details if I had stuck to my resolution to keep a diary. Unfortunately, I didn't, but I can still answer the question of which six-day race was the hardest for me: my hardest six-day race was the New York Six Day Race in 1910.

The decision to compete in the race was difficult, the crossing to America was difficult, and the race itself was difficult. When I received the invitation to the race, my son Oskar, who was five years old at the time, was lying in my apartment in Friedenau, suffering from an illness that the doctors were initially unable to diagnose. The boy was hovering between life and death. He was vomiting everything he ate, becoming more frail by the day and wasting away to a skeleton. I struggled with myself. Should I leave my child with the fear in my heart that I would never see him again, or should I stay at home and give up the race?

It was a difficult struggle between paternal love and duty, in which paternal love would have prevailed if the doctor had not assured me one day that an X-ray had clarified the cause of the illness and that the little patient would recover in a short time. According to the findings, my son had suffered a bruise to the frontal sinus, and after questioning the maid, it turned out that Oskar had fallen and hit his forehead on the baseboard in the dining room while we were away and had been feeling unwell ever since.

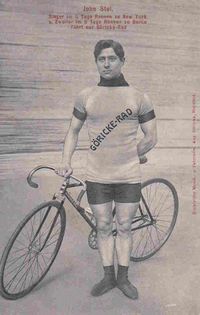

Although Oskar was still very ill, I decided to sign the contract for New York. Accompanied by my partner Stol, I set off on the journey to Paris, from where we traveled with the European six-day cyclists to Le Havre to embark on our journey across the pond. We had checked in our luggage and arrived in Le Havre in less than elegant travel suits. We were to change on the ship, and in cheerful company we waited for things to come. I was filled with concern for my son, but I was soon to be distracted by events.

When we arrived at the Messagerie Maritime, we were informed that the “Bretagne,” which had been chosen for the crossing, had suffered damage and that another steamer would have to be chartered. This other steamer was a small box of venerable age, about thirty years old, and we boarded it with some mistrust. Our mistrust proved to be justified. When we reached the open sea, the ship began to lurch, roll, and sway terribly, and soon there were no passengers left on deck. I retired to the saloon and tried to fight the seasickness, but it came anyway.

Photo: Otto Spenke, Köln

While I was struggling with the snake that was climbing up my throat, I heard Stol moaning and screaming terribly. I went down to his cabin and led him by the hand like a child onto the deck, where we decided to distract ourselves by searching for our luggage. The head steward, to whom we conveyed our wishes, referred us to the baggage handler, who searched the baggage room in every direction without finding anything. In the excitement of the futile search, we had forgotten our seasickness, but our mood had not improved.

We sent a radio telegram to a ship that had left Le Havre an hour before us, asking whether it was carrying our luggage, and after an hour we received the reply that there was nothing for Rütt and Stol on board. We then telegraphed the shipping company in Le Havre, but they also telegraphed back that they could not find anything. What now? Saddened, we retired to our cabin in the evening and the whole misery of life seemed to have overtaken us when, at around 3 a.m., we were awakened by a jolt that dispelled all our worries about the lost luggage.

The lights went out, the engines stopped, and terrible screams filled the air. I ran onto the deck, where I bumped into the wireless telegraph operator, who calmly explained to me that the weary ship had run aground on a sandbank belonging to the “ocean graveyard.” Since the ship was stationary and there was no sign of sinking, panic could have been avoided, but the darkness instilled even greater fear in the passengers, as it prevented the sailors from taking any action. Fortunately, the radio station had remained intact and the telegraph operator was busy at work. I felt my way forward in the dark to get back to my cabin when I noticed a pungent smell of alcohol.

I opened a door and saw a woman pouring alcohol from a bottle, while a little girl had to light the way with a tallow candle. I knocked the light out of the girl's hand to prevent an explosion, whereupon a flood of Portuguese swear words poured over me. Groping my way further, I came to the cabin of the racing driver Nat Butler. I found the American and his wife praying. Both were convinced that their last hour had come and, resigned to God's will, were preparing for the ship's demise. I comforted them both, and when two petroleum lamps were found, the passengers calmed down.

The ship was refloated more quickly than we had expected, and since it had not been damaged, we were able to continue our journey. The voyage would have been bearable for us despite the stormy weather, had it not been for our concern about our luggage and the laundry facing the “black death,” which spoiled our mood. On the third day, we decided to cut off the dark white cuffs of our shirts, and to prevent this act of violence from becoming the subject of lazy jokes, we kept our hands under the table as much as possible. Our experiences with our fellow travelers consoled us in our dire situation.

The French sat at a table by themselves, but we could hear their conversations very well and laugh at their jokes, unless they were so bad that laughter was unnecessary. The meal was so lively that the tablecloth showed clear signs of the lively eating style, and the table steward announced that he would have to put a waxed tablecloth on the table for the gentlemen. We heard one phrase in all their conversations, namely “Pour nos femmes.” Everything the Frenchmen did, they did for their wives. They had made the contract for New York for their wives, sailed seven days at sea for their wives, ate, drank, smoked, sang, and played for their wives; in short, every activity was done “pour nos femmes.”

We picked up on this phrase and used it at every opportunity. Soon it had become a catchphrase, and other passengers also began to use this newly coined slogan. Germain, Verlinden's partner, sat in the light well every evening and sang. He sang, but don't ask me how or what. In any case, many passengers thought there was a madman on board the ship. Germain was pleased that people thought he was crazy and continued to sing. As they approached the coast of the New World, the French joined in the chant “pour nos femmes” and, glad to have the hardships behind them, left the ship.

We, too, were glad to leave the old tub, but our concern about what would happen next was not insignificant. Our first stop was the shipping company, where we demanded our luggage. We were told that our luggage would probably arrive later on the “Savoie.” With this little comforting news, we went to our hotel and then to Pat Powers' office. The Six Days organizer was in a bad mood: customs was making it difficult to release the riders' luggage. Only after 5,000 francs had been deposited did the riders get their luggage and bikes.

While Powers was dealing with the customs authorities, we looked for a place to train and, after a long search, found two exercise bikes. I used a machine that the American Fenn had lent me and rode in my road suit. We didn't train at home for long. We went to the Vailsburgbahn, where we began a solid pumping session. My upper body was clad in a jersey from Jimmy Moran, my legs were in racing shorts from Germain, I had a cap from Kramer on my head, Foglers racing shoes on my feet, and I was riding a machine from Fenn. Although I looked a bit motley, I was more presentable than my friend Stol, who looked like a clown in clothes that were much too big for him.

Photo: Göricke Fahrradwerke

Everything would have been fine if our benefactors had had more than one set of jerseys, pants, etc. As it happened, Moran demanded his jersey back, Fogler wanted his shoes, and Germain reclaimed his legwear. I was only able to keep Kramer's cap and Fenn's bicycle, but I couldn't possibly have trained in that outfit without feeling deeply ashamed. Kramer had already offered me his equipment when we received word that the Savoie had arrived and our luggage was on board.

We immediately rushed to the harbor, and since it was taking too long to find our luggage, we set about juggling suitcases and boxes ourselves. Finally, we saw our belongings floating up to the light on the crane, and like two people rescued from a shipwreck, we left the landing stage. This happened on Saturday at noon, and on the same day I was supposed to race against Kramer and Clark. My machines weren't ready yet, and I worked in my cabin until evening. I heard the murmur of the crowd outside, the cheers of the enthusiasts when one of their favorites appeared, but I didn't let it bother me.

Suddenly, Pat Powers rushed into my cabin and told me to come to the start. I quickly got changed, took my bike, and lined up at the start. Although I was well trained, I couldn't overcome the excitement of the last few days and had to admit defeat in both races. However, my hopes for the six-day race did not diminish, and after working on our bikes on Sunday as well, we lined up at the start. The first few days passed without any particular excitement. The pace was very fast, but we took turns very precisely and got through everything.

The French riders were the most aggressive, and I can say that Verlinden in particular disappointed me greatly. I thought the Belgians were good six-day riders, but he didn't last long and the battle cry “Pour nos femmes” became increasingly rare. When Pouchois was “on his last legs” and could barely sit on his bike, I shouted “Pour nos femmes” to him, but he no longer responded. The Americans soon picked up the battle cry and used it without knowing what it meant. Every time the field passed the French camp, the cry “Paur nau Fäm” rang out, and when Pouchois was completely dead, this cry accompanied him to his grave in the cabin.

The first incident in the race was our loss of two laps. Much has been written about this incident, but no newspaper has given an accurate account, and this has put us in a position that could cast Stol in a bad light. When the chase began on Thursday morning, we were in the lead. Suddenly, Clark suffered a flat tire and swayed so badly that he endangered the other riders. I immediately ran onto the track, as I thought Stol was in danger, and to my astonishment, I saw the field storming away without paying any attention to Clark's flat tire. Assuming that the race would be called off, I shouted to Stol to stop, which he did immediately.

The view that Stol misunderstood my signals is therefore incorrect. He followed my advice; under normal circumstances, he would never have lost two laps. We were astonished when, at the end of the hour, it was announced that we had lost two laps and that Clark-McFarland had fallen back by one lap. I protested. I received no response, but instead Powers came to me to inquire about what had happened. I explained that we would give up if the laps were not credited to us, whereupon Powers asked me to stay in the race for the time being.

What I could not understand was the unfair treatment of the McFarland-Clark team. We continued, but I had little hope of making up the lost laps and I resigned myself to the idea of giving up the race. Things changed faster than I had thought. McFarland appeared in my cabin, claiming to be completely exhausted, wanting to give up and leave his partner to me, with whom I would have a better chance of making up the lost laps than with Stol. I declined, as I couldn't abandon Stol, and went to the track to talk to my partner.

Stol, who had heard of McFarland's intention, explained to me that he didn't want to hinder me and would give up, as he didn't feel strong enough to make up the lost ground. The way to a merger with Clark was clear, and in half an hour everything was settled. I moved to the American camp and now believed I could rest for four hours, as the driving regulations stipulate that a driver whose partner has been eliminated has four hours to find a new partner.

I was wrong. The Americans protested, and I had to continue the race without a break. I didn't mind not taking the four-hour break, but in Clark's interest, I would have liked to have taken it. The little Australian had had to drive a lot in the four days because McFarland had not been on duty. He seemed a little strained to me, but when we took turns regularly, he regained his strength and we set our sights on big things. For me, it was clear that I had to make up the laps, whatever the cost, and Clark also showed great courage.

We informed McFarland, who had reappeared on the track after a short sleep, of our plan, and preparations were made in silence. Wheels and tires were laid out, clean jerseys were taken out of the cupboards, oxygen apparatus was set up, and everything was put in order. The battle could begin. Mac Farland wanted to go to Powers' box, and we were to start the moment the Californian dropped his hand on the railing. I looked up at the box every lap, but Mac's hand did not fall.

Suddenly, we saw Mac jump up and rush out of the box. At the same moment, managers from all camps emerged with new jerseys, tires, wheels, and other equipment, and to our astonishment, we realized that our opponents were prepared to defend themselves. We had been betrayed, that much was clear, but we didn't know who had committed the betrayal. When Clark replaced me, I was about to go to my locker room when I heard cursing and wailing. I walked over and saw the tall Mac mercilessly punching one of our coaches.

I felt sorry for the pitifully beaten coach and called McFarland, who told me in a state of extreme agitation that our own coach had been the traitor and had received his just punishment. McFarland had been able to observe from his box how the coach had sneaked into the racing camp and mobilized all the drivers. Now I understood the Americans' sneering grin when I got off my bike. The first attempt had failed due to our coach's betrayal, but we didn't let our spirits sink and pushed forward without much preparation.

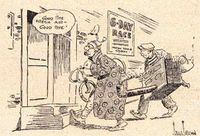

Cartoon by Howard Freeman

The American pairs stuck together. They supported each other in defending against our attacks. But this perception did not discourage us, and we entered the new day with high hopes. McFarland informed me that there were various “brakers” in the field and that I should be on my guard. I trusted the referees, who had already canceled a lap that had gone to Root-Moran thanks to cooperation among the Americans, and stayed behind Fogler. Suddenly, I heard shouting: when I looked up, I saw Fogler's grinning face. I soon noticed that Hehir and Root had pulled away from the field, but no rider made any move to chase them.

There was heavy braking when I tried to follow, and in five laps Hehir and Root were back in the field. The crowd was noisy and protesting, and McFarland went to the finish line judges' box to lodge a protest on our behalf against the Americans' behavior. The drivers and managers pulled down “Long Mac's” raised arm to prevent the protest, but as soon as the Californian turned around and assumed a boxing stance, they ran away. Clark relieved me and I went to my cabin. When the result was announced, I was quite astonished to learn that we had lost another lap, putting us three laps behind. McFarland explained to me that the protest against Root had been rejected and that we had to accept the inevitable.

While we were still talking about it, Fogler, whose rear wheel I had held during the lap by Root and Hehir, came over and said with a laugh, “I'm a lucky guy, they lap me and I still stay in the leading group. You can't ask for more than that.” These words from the American showed me the direction the race was going to take, and I decided to do everything I could to cross that path. I was furious about the injustice that had befallen us and swore revenge. Once we gained half a lap on the second group, but the first time Walthour crashed and the second time Drobach, Fogler, Demara, and Halstead fell.

During the second chase, we had already lapped several pairs, but our lap gain was not recognized and all our work had been in vain. However, the attacks had worn down our opponents so much that we were able to regain the first lap at 1 a.m. We had ridden for twenty-five minutes as fast as we could, and never in my life have I heard people scream like they did during that time. Never in my life will I forget Moran's face when he saw me appear next to him. He sat hunched over on his machine and greeted me with a terrible scream.

I had the impression that Moran was exhausted, and I encouraged Clark not to let up. We kept our opponents on their toes all night long, and the audience remained in their seats. At 5 a.m., there were still about 10,000 people there, which had never happened before in New York. We achieved our goal, and Root was soon so exhausted that he could barely get on his bike. At 6 a.m., when Hill replaced his partner Fogler and Moran spoke to Fogler, I took off. Before the Americans realized what had happened, I had lapped the field all by myself. Ten minutes later, I took off again.

This time, I didn't manage to overtake the field on my own. Clark rode like the devil, but the wild chase was after him, and I was about to give up the fight when Clark gained a lead. Now we continued the chase, and inch by inch we gained ground until we had caught up with the third lap and reached the leading group. I have been involved in many chases in my life, but I have to say that the chase in which we gained two laps in twenty minutes was the hardest I have ever been involved in. We were now in the leading group and had a chance of winning, but I believed that they would not leave us alone. Our opponents were exhausted, but we were only human too and couldn't expect superhuman feats from ourselves.

The Americans' despondency was greater than I had thought. As we passed the Moran-Root camp, I heard the usually undaunted Moran call out to his partner: “Let's give up!” I knew that this was a momentary weakness that affects every six-day rider, and I didn't expect Moran to give up, but it was clear to me that the other riders had been worn down. After the chase, calm returned. As soon as I got on the track, some rider pushed his way up to me to ask me about Germany. The Americans had heard about a six-day race in Cologne and asked me during the race to recommend them to the race organizers.

I promised to do what I could to get rid of the tormentors. Hill, who has a voice like a five-year-old child, stayed by my side for a long time and chirped in my ear. I christened him “Piepvogel” (chirping bird) and soon his compatriots were calling him “Piepfaugel” (chirping bird). There was a lot to laugh about. Collins is known to be very thin, so the newspapers called him “the human hairpin.” When Drobach wanted to be relieved by him, he called into his cabin, “Where is Collins?” to which Moran replied, “He's hiding behind the air pump.”

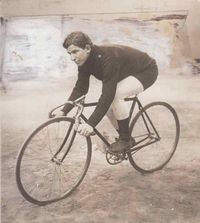

Photo: M. Rol, Paris

By the way, Drobach. I have seen many energetic riders, but Drobach really amazed me. The German-American is an educated man and a good rider who is not to be underestimated as a six-day racer, but he is unlucky. When he fell during a big chase, he broke his collarbone. He refused to give up the race, continuing to ride despite the pain, and we took pity on him. However, this could not go on for long, especially since Drobach was unable to keep up when a rider accelerated because he could not pull on the handlebars with his injured arm to give the pedals more power.

Drobach knew how to help himself. He tied a rope across his back and attached it to the handlebars. As soon as he had to accelerate, he pressed his back against the rope and kept up quite well, but when he could no longer bear the pain, he gave up. I was told a very funny story during the race. When it became known that Stol had given up, some young people had the idea of pretending to be Stol to the inspectors in order to gain free admission. When five fake Stols had smuggled themselves past five different inspectors, Powers gave the order not to let any more “Stols” in.

Then a small young man appeared at the entrance and asked to be let in. “What's your name?” asked the inspector. “Stol.” “What, Stol? Now get out of here, you're already the sixth Stol. We're not falling for that scam anymore. Get out!” The inspector took the young man by the arm and literally threw him out. Knowing he had done his duty, he returned to his seat, unaware that he had thrown out the real Stol, who had no idea of the abuse that had been perpetrated in his name. The little Dutchman had no choice but to buy a ticket to get into the hall.

During the quiet period, I got to know my opponents better and I must say that I found some of them to be very charming guys. The intrusion of the Australians as six-day racers was remarkable, as no fewer than five Australians were in the race: Hehir, Goullet, Clark, Pye, and Walker. I was told great stories about Hehir. I had already gotten to know the Australian during the race as a reckless and daring rider, but I didn't know that he had even brought down Frank Kramer and Fogler, two very skilled riders. Once he had been left behind, he worked his way through the field with breathtaking recklessness and reached the leading group.

On the Vailsburg track, Fogler had once been knocked down by Hehir, and in his anger, Fogler took his bike and threw it at Hehir as he sprinted out of the corner. However, the throw had no effect, even though Fogler's projectile hit its target, because the exceptionally confident Australian jumped over the machine with his bike and finished second. The hours passed and the end of the race drew nearer. I consulted with McFarland. I told him that we still had to win one more lap, but “Long Mac” had reservations. He believed that we couldn't lose the race if I spared Clark and left the final sprint to him. I protested, but “Mac” persuaded me to entrust Clark with the final sprint.

I rode for about nine hours of the last 12 hours to spare my partner, but I made the surprising observation that the Americans were getting fresher and fresher. My heart was heavy, but I didn't dare make a move to win a lap because Clark, who had been woken from his sleep, would not have supported me as I wanted him to. So the end of the hardest of my six-day races was approaching. I felt uneasy when I saw little Clark enter the decisive battle, but Mac was confident. Clark's young wife stood next to me during the decision, and when she saw her husband being beaten by Root, she fainted.

Image of the medal Walter Rutt received in memory of Floyd McFarland's memorable six-day race. The cat's head alludes to Rütt's nickname, “Bearcat.”

I didn't know whether I was dreaming or awake, but unfortunately it was reality, and, bitterly disappointed, I left the hall filled with deafening noise. I found it very difficult to recover from the exertions of the race. I couldn't stay in America because Christmas was just around the corner and I had a sick son at home. Stol told me he wanted to stay in America to look for opportunities to compete, so I went to the harbor alone. As I was about to board the ship, I read on a notice board that the steamship “Kaiser Wilhelm der Große” had lost a propeller on its voyage to America and would have to make the return journey with only one propeller.

That was another disappointment, because I was in danger of not being able to get back to Germany in time for Christmas. Hoping that everything would turn out all right, I entrusted myself to the disabled ocean giant and, after a very pleasant journey, I reached Bremen a day and a half late. Despite the disappointment in New York, I can safely say that I was one of the happiest people after my return. For the first time in a long time, I stood under a German Christmas tree in Germany and enjoyed the most beautiful Christmas present I have ever received: the recovery of my son Oskar from a serious illness.

Note

The article is taken from the book “Six Days on the Bike” by Fredy Budzinski.

Copyright © 2005 - 2026 Bernd Wagner All rights reserved